hiking guide

"Hike at your own risk"...needless to say, people have died here due to the geography and weather. Granite surfaces can be slippery. The weather can be hazardous even in the spring and fall, when temperatures can drop from 80 to below freezing in a few hours. Winters can be very hazardous, with sudden snow and winds over 100 mph. The altitude ranges from 6200 feet at the lake to 7100 feet at the summit and can wear you out if you're not used to it.

Above is an aerial view showing, in green, the State Highway prior to Highway 40...from the west end of Donner Lake (at Old Highway Drive) to the summit. This same route was also the 1863 Dutch Flat Donner Lake Wagon Road (the blue line was part of the DFDLWR and moved in 1914).

This is the probably most exact map ever made of the road in this section, using the recently discovered 1915 state map and survey, and overlaying it on a Google view.

Note: In this aerial view and the one further down, the green line covers up the old road, which is mostly visible in these Google aerial views.

"How do we find this road?"

Going downhill from the Pacific Crest Trail:

Trailhead is near the original Donner Summit, latitude 39.314540 longitude -120.326900

In the summit area, the PCT crosses Old Highway 40 at the summit--you'll see the Sugar Bowl Ski Academy. The PCT continues southwest on a short gravel road for about 800 feet. It then comes to a T--which is the old road--the Lincoln Highway, the Dutch Flat Donner Lake Wagon Road, and the Emigrant Road. It is actually named "Old Donner Summit Road." The road to the right is paved, going west to Lake Mary, crossing Sugar Bowl Road, and continuing to Soda Springs and beyond. To the left is the PCT (left photo below), which is dirt and gravel. About 130 feet from there, you'll see another sign (you can barely see the sign in the photo) which refers to the PCT continuing to the right. But veer to the left to continue on the old highway. That "intersection" is the summit of the old road. The next 900 feet of the old road was cleared of brush in 2009. It can be walked somewhat easily now. Doesn't look like much now, but in this part of California, this was the only "interstate highway" and this was the only summit for 81 years, 1844-1925.

Going uphill from Donner Lake:

The unpaved portion of the public road begins at the west end of Donner Lake, between 16306 and 16352 Old Highway Drive, off of South Shore Drive. The old highway looks like a small gravel driveway but is very visible.

After 800 feet, you'll reach the point below...what used to be the rock barricade. After 21 years, and despite years of attempts by corrupt local politicians to keep the public off of this public road and give it over to a private party, we succeeded in opening it up to the public as of August 2011. The threatening signs on the trees warning of Rottweiler dogs have also been removed.

You can also start the hike at the new kiosk parking lot off of Old Highway 40 (now Donner Pass Road). It's about a half mile up from South Shore Drive.

A little further, you'll come to two forks...here is the first:

The bridge down from the kiosk parking area is a side trail...it's not the Dutch Flat Donner Lake Wagon Road and old state highway...keep to the right.

Next, you'll see another fork in the road shown below (the fence has since been removed). The road to the left (the orange line in the view below) is a bypass and not part of the old highway. It crosses Summit Creek at a point where more water is flowing, but after spring, the flow subsides and it may be an easier walk. On the highway to the right (the green line), after walking the obvious road visible above for about 350 feet, you'll encounter a brushy and eroded area. "Just" work through that 150 feet or so (expect nothing that looks like a road) and you'll get to the straight section where the spring stream has diverted onto the road. If there is still water in the road in the spring and early summer, walk alongside it towards the southwest and at some point, cross the stream and get back onto the road near the point where the bypass trail joins it. If it's any consolation, a 1910 map warned drivers that this area is "Rocky."

Below is a closer view of the lower half of the road to the summit.

Glad to report that both the trailer and boulders that once blocked the road are now gone

Spots on the old road to navigate around:

In addition to the area described above, and going around the washed out bridge described further down this page, there are 5 other spots that you'll need look for--all are in the area near the summit, shown in the photo below. The green line shows the state highway as it was surveyed in 1915, just one year after the underpass was completed under the railroad tracks. The blue line is the 1864 Dutch Flat Donner Lake Wagon Road. The red line shows the temporary 1925 detour (the red line is just left of the actual road, so that the old road can be seen here).

The top of this photo is towards the west.

Above and below, 1916.

Everything was taking off in 1915-16 due to the car.

(listed in order going uphill)

A: In the section of the old road below the rock-climbers favorite spot (where there is the plaque about the Chinese workers), the road to the east of the plaque has 2 to 4 foot boulders covering the road for about 100 feet (a result of the 1970s gas line trenching). To the west of the plaque, for about 100 feet, the old road is overgrown with brush and eroded due to water flowing onto the old road but a narrow trail can be walked.

B: Just northwest of that area, as you climb and get close to old 40, the old road is technically right next to Old 40, but is buried under the support fill for Old 40. You'll be walking on the temporary 1925 road that is a a few feet to the west of the actual old road--it was used while Highway 40 was under construction.

C: Just northwest of that area, you'll see a pond. The old road went along the southwest edge of and through the current pond (this pond did not exist before 1925--old photos show small houses on this flat area--see right; there was--and is--a marshy area on the other side of the old road). The dirt was removed for fill for Old 40. During the 1925 construction of Old 40, rocks fell down onto the old road that hugged the steep mountainside. To avoid the falling rocks, in 1925, the state built a detour away from the mountainside and over the granite hump (red line in photo below). You can find it with a little effort, look for a path carved out of the brush.

D: Once you cross the granite hump, you'll be back onto the original road. The road in this area was raised about two feet since the 1860s due to the marshy ground. Just above the letter D in the photo above, look for the 2-foot high concrete supporting walls in this area on both sides of the road to raise the road. Before you reach the recent (1960+-) ramp made of small rocks, the old road veers to the right. You'll see a path through the brush. It then continues into what looks like a rocky dry creek bed. Go about 150 feet to the west. This section is where the two wagon trains are seen in the 1866 photo on the 1800 Photos page.

E: If you're going up the pre-1914 incline to reach the railroad (blue line above), you'll find a pathway through the brush where the letter E is in the photo above. After the left turn against the rock wall below Old 40, you'll see a light green '67 Mustang crunched up into a small chunk of metal (there's no room for a body inside the crunched-up interior and the doors are jammed closed, so the car was probably pushed off rather than driven off Old 40, unless someone was ejected out a window as it bounced down before it hit bottom). After the Mustang, you'll need to make your way around three or four 4-foot boulders that fell down when Highway 40 was built.

F: Near the top of the incline, close to the railroad bed, you'll need to climb about 4 feet over some small boulders. A few feet past that, you'll reach the concrete snow shed, which somewhat blocks the old road--but you can walk around it. From there, the old road goes across the railroad bed and then up around the rock outcropping (see blue line above). Make your way through this recently cleared area and you'll merge onto the main old road.

If you're not going up the pre-1914 incline, back at the junction of the 1914 and pre-1914 road, head for the 1914 incline (green line above) to the auto tunnel to reach the same spot. The brush has overgrown the 1914 road between the junction and the incline so just walk on the granite to the incline.

Once you're at the main visible road south of the railroad area, at the junction of the 1914 and pre-1914 roads, walk west 1,122 feet of very easy straight road and you'll reach the original 1844-1925 summit.

Our January 2009 snowshoe hike along the Donner Trail

(during a snowstorm)

Our snowshoe group only made it up about 1/3 the distance from Old Highway Drive to the summit. We turned around seeing more dark clouds coming in and the temperature quickly dropping. Trekking through the fresh snow was not easy, even with our modern snowshoes. But the most difficult part was crossing Summit Creek, about 15' wide and one foot deep of rushing freezing water. We removed our snowshoes, boots, and socks so we could cross the stream--the same stream the Donner Party and all others would have had to cross, along with some smaller streams before it. We were probably doing exactly the same thing they did, realizing it would be better to remove our boots while crossing the stream than to get them wet and freeze on our feet.

Picture yourself sitting in snow on the bank of the stream, removing your boots and socks while snow is coming down, walking across the stream carrying your snowshoes, boots, and socks along with whatever else you're carrying, carving out some type of steps on the 4-foot vertical bank of snow on the other side while standing in the freezing water in bare feet, climbing out and then sitting in the snow to put on your socks and boots. By the time we crossed it again coming back down and trekking back to Old Highway Drive, we were worn out. It's easy to see why the Donner Party wouldn't have wanted to tackle that again after their first attempts, yet the mostly successful snowshoe group tried again several weeks later on December 17, 1846, in even more snow. We could also see the other problem (really the main problem) the Donner Party had--losing track of the trail in the mostly flat area under 4-6 feet of snow, where we are shown above near the creek crossing--it was only because we had seen it so many times without snow that we knew where to walk. Staying on the trail is essential even in summer. If you deviate from it, you may be able to walk a few yards, but you'll soon run up against vertical walls or a mass of trees.

Our hike was a definite learning experience, and it was certainly scenic...

But in the summer, it's a totally different world:

Along the trail in the mostly flat area halfway from the lake to the summit.

This is the point where the "northern route" and the "southern route" split on the way up to the summit. The 1915 state highway surveyor noted as he passed this spot that the "abandoned" (the northern) road went to the right. The yellow ribbon indicates the junction.

Both routes cover a quarter-mile section of travel midway to the summit. The northern route is the older road built sometime between 1849 and 1863. (further down on this page is an Anthony photo from1862 or 63 that proves the northern route was built before the 1863 southern route).

The Northern Route

Above, the pre-1863 northern route in 2010, showing 30-foot high vertical supporting wall, with Jack Duncan, author of "From Donner Pass To The Pacific."

The northern road was (and is) steep, rough, and dangerous in spots. Neither route was the trail used by the Indians and the Stephens party (and Donner party survivors) and other very early pioneers, since blasting of steep granite walls was needed to create portions of the roadway for both routes. Indians didn't build such roads for wheeled wagons since they had never invented the wheel. The only other route up this mountain was in the dip between the two routes and joined in just left of the red pole in the photo two below (there are boulders placed across this dip to keep vehicles out. This route requires a steep yet somewhat smooth climb and joins into the point where the other two routes join together. This dip is shown below, with the rocks along the edge of the Northern Route on the left. The old "Donner Pass" painting below appears to be in the same spot.

Above, another angle of the same spot. The washed-out bridge that was needed for the Southern Route is behind the tree behind the yellow and red stakes (fiber optic and gas line markers).

The Southern Route

By 1863, the Dutch Flat Donner Lake Wagon Road builders (aka the Central Pacific Railroad) realized the northern route was too steep and carved out an easier route across the valley to the south, allowing extra length for a more gradual climb. That route required a small bridge (about 12 feet long and 10 feet deep) near the western point where the two joined up again. That wooden bridge was probably replaced several times (the 1915 state surveyor noted as he passed the bridge that the boards needed replacement) and finally washed out in 1960 and has never been replaced, although the stone footing is still in original shape. Therefore, the southern route, which was also the official state highway from 1909 to 1926, has been unused by regular vehicles since 1960 and some of it is overgrown with brush and small trees.

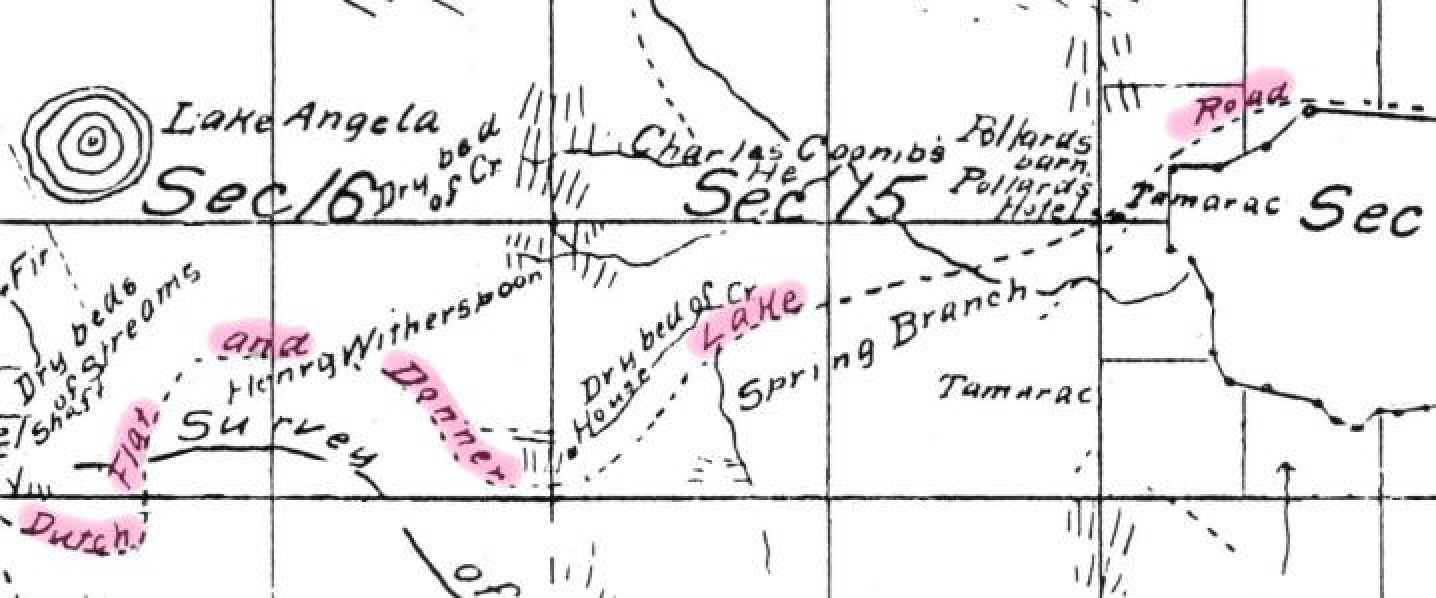

Both routes continued to be used and show up on all old maps beginning in 1866. Below is a detail of the 1866 survey, the first known survey of the area, labeling the Dutch Flat And Donner Lake Wagon Road (highlighted in pink). It is not very exact but it clearly shows both the northern and southern route with the southern route being the DFDLWR, which opened two years before the physical survey for this map. The northern route is shown with the 3 dashes going to the right between the two "n" letters in the word "Donner" (compare to the map at the top of this page). Hard to read words are "Dry beds of stream" and "Dry beds of Cr(eek)" and "Charles Coombs House (a "house" was a term for a station or small motel) and "Henry Witherspoon House." The dot next to "House" indicates the place. This was also known as Witherspoon Station, owned by John Henry Witherspoon. He was a civil and mining engineer by profession, and was in charge of the building of the DFDLWR. He and his family lived at this spot for three years. He was married to Elizabeth Halligan. Their son Henry Eugene was born here June 30, 1866 (the year of this map). Two other sons died in infancy. Henry Eugene later became a famous water and mining attorney in SF. John Henry, the father, was believed to have been killed by Indians in Arizona. The site is just to the west of the next 2 photos below--notice the dry creek bed.

Back at the split (the earlier photo with the yellow ribbon), about 300 feet south of that point is the left photo...current hikers need to cross a bumpy 50 feet or so where a spring stream flows...it's the same creek in the same spot as the 1873 Montague & Clement map shows (see Maps page). It has washed away the top layer of road over the years and created two minor gullies (1-2 feet deep).

Head for the huge boulder (right photo...written about in the 1903 article below). Once you've passed the gullies, the road will be easy to walk from there on, with a few spots where you need to navigate through some small trees.

The National Tribune, Washington DC

Sights of California by W.W. Stone

July 30, 1903.

Truckee is the first place where overland tourists get a chance to observe California life. The trains stop here long enough for passengers to get a meal. The town is alive with strenuosity. In the early dusk it is filled to overflow with miners, millmen, hunters, railroad employees and idlers. You can get bear meat from the mountains, fish from the river, venison from the hills, and fruit from the orchards.

One gathers energy from the air in such a place, so that on Friday morning, after a hearty breakfast, I threw my rifle over my shoulder and started a-foot for the Summit. My path lay past Donner Lake, a beautiful sheet of sparkling water, midway up. Here I stopped for a while to fish, with moderate success. The wagon road from Donner Lake to the Summit was a source of frequent surprises. At one time a huge boulder, as large as a moderate-sized cottage, stared at me in the face from the middle of the road; farther along a miniature river dashed across my pathway.

Notice that on nearly all of the road, there are the original one-to-two foot boulders lining the edge of the road, and creating a drainage channel on the uphill side of the road (photo below). The older northern route doesn't have this design.

This section of the old road is right up against a granite mountainside, which can have avalanches during the winter. In the winter of 1864-65, two "wagon road repairers" were buried and killed by a slide in this area, the same area where a year later "at Tunnel No. 10, some 15 to 20 Chinese were killed by a slide" while working on the tunnel. They weren't uncovered until spring. The photo above shows this area that is mostly unchanged since that time.

After about a quarter mile west of the huge boulder, you'll reach the point below. As you walk on the southern route around this granite bend, notice the engineering compared to the northern route. It was built in 1863 as part of the Dutch Flat Donner Lake Wagon Road at a cost of over $300,000 (in 1863 dollars), and when it opened, was one of the best mountain roads anywhere.

Above, looking north today along the old State highway that hasn't had regular traffic since 1960. The road and the supporting rocks have been here since they were built in 1863. This is the most pristine section of the old highway--with virtually no change over 150 years. The washed out bridge is just around the bend. Four different routes can be seen in this photo. If you know where to look, you can see the northern route across the ravine, going up to the left at an even angle, and above that road is old Highway 40--look for the guardrail. Also, the original Indian/early pioneer route is in the right one-third of the photo, going up at a 45-degree angle (just the other side of the supporting rocks--look for the yellowish brush and the straight line of boulders placed across the road). This spot is about 1/2 mile down from the summit. The State of California and Placer and Nevada Counties own the roadway here...the US Forest Service owns the surrounding land.

Keep an eye out for what used to be the bridge...you could walk right off the edge if you're not looking and take a 10 foot drop.

After the stream dries up in early summer, there is a walkable route about 40 feet next to the bridge footing (the summit side of the bridge). You need to cross the stream bed, which can sometimes be done even when water is flowing.

Above left is an Anthony photo taken before the photo on the right, which proves the Northern Route is older. The photo on the right has the bridge built for the Southern Route, the official Dutch Flat Donner Lake Wagon Road and used as the state highway until 1926. The Anthony photo also shows the construction trailer used for building the bridge.

Notice the small white sign on the the tree at the "Y". It probably had some information about the two routes. That tree is the same one as the one above behind the red pole.

Notice no guard rails on the bridge. There were no such things as guard rails back then, even on the high dangerous curves in this area. You took your chances with what was there.

And notice all the utility poles. This small area channeled people and utilities to and from California then and now, with current natural gas lines and ATT's fiber optic lines going through this narrow strip, along with Old Highway 40 a few feet to the left of the photo.

Above left photo, a few feet to the left of the "Y" showing the current Northern Route. Above right photos show the current "Y" and an old car taking the Southern Route.

From 1864 until Highway 40 opened in 1926, the older northern route probably continued to be used in the winter and spring when snow and risk of avalanche made the main southern route impassible since it was right up against the mountainside, while the sun melted the snow weeks earlier on the northern route.

Nearly all of both routes go through US Forest Service land, however, the Forest Service does not own any part of the old 1909 state highway and has no authority over it (they cannot "close" it nor "open" it). Just as with old Highway 40, all of the old 1909 state highway, including the pre-1914 over-the-tracks route, is a 50-foot wide strip of county property (Placer and Nevada) and Town of Truckee property with the State of California retaining "latent" stock-trail ownership. In addition, since the 1800s, 200 feet on either side of the railroad track bed that isn't the county road is owned by the Union Pacific Railroad.

Can you match these people back in 1886, hiking from Donner Lake to Lake Mary, then to Donner Peak and back in one day--for fun. Notice the reference to "the summit road"...that is the DFDLWR.

The Sacramento Daily Union

A Trip to Donner Peak.

Truckee. July 28, 1886.

Last Wednesday morning a party of sixteen from Donner Lake united in a picnic expedition to Donner Peak. Following up the summit road as far as Lake Mary, some engaged in gathering flowers, and others, admiring the grand scenery of the summit peaks, towering up like some grand castle, far above the snow sheds.

After leaving Lake Mary the party proceeded a short distance, when lunch was served out under pine trees, which aided the mountain air as an excellent tonic for sharpening appetites. The party then proceeded up the mountain trail near the summit of Donner peak, passing over a large bank of snow. Here a gay game of snowballing was indulged in by the entire company. After fully ascending Donner peak, some grand scenery was presented to view. In the distance could be seen Truckee, Martis Valley, Tinker's Knob, Castle Peak, Summit Valley, Red Mountain, Devil's Peak and six lakes. From off this peak fair Donner reminds one of a mirror spread out beneath amid the mountains.

The party, satisfied with sightseeing, returned to former levels, greatly pleased with the trip. The party consisted of James Stuart, Hector Stromberg, George Mills, Frank Tomlinson, Lewis Tomlinson, Joseph Tomlinson, Ida L. Tomlinson, Mattie Tomlinson, S. Willet, Tom Martin, Albert Harney, Edgar Newkirk, Mrs. James S. Curtis, Mrs. Martin, Kate Hyde and Maud Martin.

Coming soon...Take amazing Google Earth 3D "fly-over" tour of the old road from Donner Lake to the summit, following the official 1915 California Highway Survey!